Ingeniero Jacobacci, Argentina, is the Congregation’s southernmost mission and part of the Claretian province of San José del Sur. This place is also known as Wawel Niyeo, which in the Mapuche language means “place where water springs forth“.

If one travels a few kilometers from the small villages in the area, one could say that this community is “in the middle of nowhere”. This expression is often used to convey the incredible immensity of these places. However, it fails to do justice to the landscape or to the missionary, historical, ecumenical, and vital work carried out in these lands.

The Claretian Missionaries have been walking through this territory for more than five decades. Their fidelity to the way of living the mission can be seen in the work with others that has been developed in this periphery and that currently has its counterpart in the articulation with organizations of the Mapuche people and inhabitants who, regardless of their expressions of faith, share the path in the construction of the Kingdom.

Wawel Niyeo is part of Wallmapu, which is ancestral Mapuche territory. Long before the existence of modern states, between the Atlantic and the Pacific, in what we now know as the Argentine and Chilean Patagonia, with the Andes mountain range as a witness, various factions of the Mapuche people lived, moved, traded, and maintained their own community organizations and cultures. The consolidation of states and the need for territorial expansion towards the end of the 19th century led both Argentina and Chile to launch military campaigns – with the support of the Church at that time – to expand their borders to the south. This process of expansion required and was based on a cruel genocide against the Mapuche people, who still today demand that the Argentine state take responsibility for the crime perpetrated against the pre-existing people.

Within this history and these scenarios, specifically in these lands, the Church in the southern hemisphere became an indispensable actor, working to repair the institutional harm inflicted on an ancestral people. Embraced and supported today by the teachings left to us by Pope Francis, the Church has requested forgiveness for the crimes it has committed against these peoples, by action or omission. It is also a church that has been reaping the fruits of the seeds sown by the Sons of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in these latitudes for more than 50 years.

Once the military campaigns that led to the genocide of the Mapuche people on both sides of the mountain range had ended, the extermination continued with policies to make them invisible that included prohibiting them from speaking their native language, dressing according to their traditions, or celebrating their ceremonies. It was a territorial but also a spiritual dispossession.

In the 20th century, the survivors of that genocide, who transformed into small livestock producers occupying small, unproductive plots of land, devoted themselves to raising sheep and goats and were victims of state and community practices that kept them in poverty and exclusion. In this context, the church to which we refer emerged: the one that, on our continent, inspired by Latin American Bishops’ documents of Puebla and of Medellín, resisted military dictatorships and became a servant of the causes of the poor.

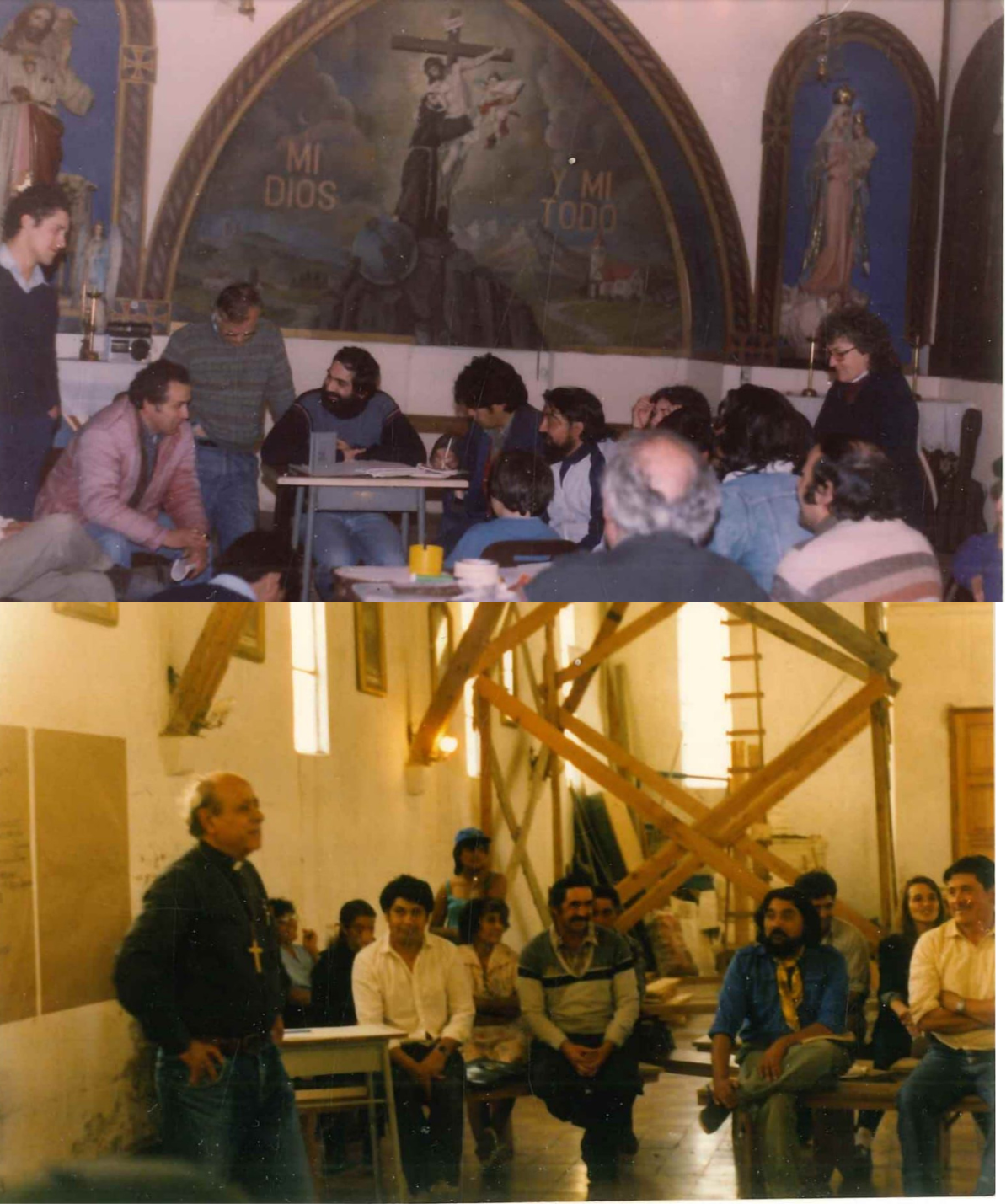

A milestone that also serves as a legacy for those of us who walk in the mission today was the enactment of the Comprehensive Indigenous Law of the province of Río Negro in 1988. At that time, Father Francisco Fernández Salinas (Father Paco), a Missionary of the Sacred Hearts, opened the doors of our San Francisco Church to become a ruka (house, in the Mapuche language) ready for deliberation and organization. On the Claretian side, and in another neighboring area of this Southern Line, Fr. Carlos Calgaro resolutely accompanied this process, prioritizing tasks for the foundation and consolidation of Livestock Cooperatives throughout the region.

From that coordinated work, with a strong Cordimarian tradition, this missionary community believes that one cannot be a Claretian and live as if the poor did not exist. Nor can one be a Claretian without denouncing structures of injustice.

The work that the Claretian Missionaries carried out in the communities near Jacobacci contributed to the organization of the Mapuche people in pursuit of practices that do not clash with their ancestral traditions, the creation of legislation that takes into account interculturality, and the rescue of their ancestral language – since, as an illiterate people, all cultural/spiritual transmission is based on oral tradition.

More recently, a fundamental task that accompanies the Congregation is the defense of Water and Territory. But… why this slogan?

The worldview of the Mapuche people, like that of most ancestral peoples around the world, considers that everything animate and inanimate with which we coexist is part of a delicate balance that must be preserved. And suppose we delve a little deeper and set aside the colonial and colonizing view that these people have been subjected to. In that case, we can say that each element of Creation has its own governing force, that everything is interconnected, and that everything has its way of being present in our lives.

Around the year 2000, transnational companies began to gain strength with the intention of extracting common goods from the subsoil. The actions of such companies clash with the Mapuche worldview. Can we ask a people whose temple is the Common House to allow such destruction? For the Mapuche people, the territory is the temple of Creation; it is the open air where all the activities that give material and spiritual sustenance to their lives take place. They consider water (as we do) a common good indispensable for rituals and for future generations.

As a Claretian family, we have also been accompanying the cry for the care of our Common Home from the cry of people experiencing poverty for more than two decades. The articulation from the JPIC perspective with ecclesial and community actors allowed us to participate in spaces of reflection and action that respond to the experience of the incarnate Gospel, positioning ourselves from the place of the poor and charting a path accordingly.

Suppose we pause to consider the encyclical Laudato Si’, in the section where Francis refers to large-scale mining. In that case, we see that it is based on the reflections of the Bishops of the Patagonia-Comahue region at Christmas 2009. It arises from this latitude, from these people. In other words, the journey of faith of a community, accompanied by its pastors, many of them Claretians, in fidelity to the Gospel, inspired by Saint Anthony Mary Claret, from the end of the world, materialized in the Social Doctrine of the Church.

The Claretian Mission at the end of the world can be seen as a starting point, for it reaps the fruit of the seed our ancestors sowed in fertile soil. It walks alongside the persecuted, the excluded, and the invisible, because it risks everything for life in abundance for all, and because it wants to be that church that burns with charity and ignites a fire of love wherever it goes.

By Claudia Huircan